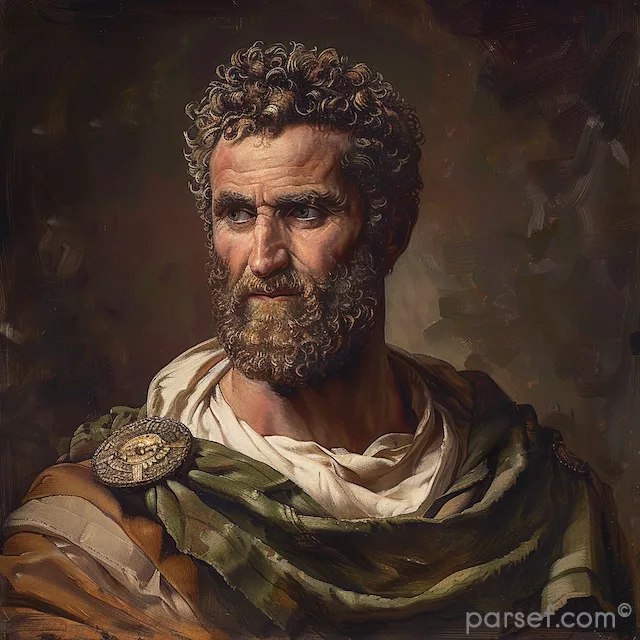

Roman Emperor Caracalla (198-217 CE, co-emperor with Septimius Severus until 211 CE)

Caracalla: The Brutal Visionary of the Roman Empire

Caracalla, born Lucius Septimius Bassianus on April 4, 188 CE, was a Roman emperor whose reign from 211 to 217 CE is remembered for both its significant legal reforms and its extraordinary brutality. He was the son of Septimius Severus, the founder of the Severan dynasty, and Julia Domna, a member of a prominent Syrian family. Caracalla’s rule marked a period of intense military activity, ruthless internal purges, and ambitious legal reforms, particularly the Constitutio Antoniniana, which extended Roman citizenship to nearly all free inhabitants of the empire. His reign, however, was also marred by acts of extreme cruelty, including the infamous massacre at Alexandria. Caracalla’s legacy is thus a complex one, defined by his contributions to Roman law and citizenship, as well as by his violent and autocratic tendencies.

Early Life and Background

Caracalla was born in Lugdunum (modern-day Lyon, France), during the early years of his father's military and political career. His father, Septimius Severus, was then the governor of Gallia Lugdunensis, a position that provided the young Caracalla with a privileged upbringing amidst the Roman elite. His birth name, Lucius Septimius Bassianus, reflected his father’s lineage, but he was later given the name Marcus Aurelius Antoninus to strengthen his connection to the esteemed Antonine dynasty, from which his father claimed a form of adoptive descent. The nickname "Caracalla" came from a type of Gallic cloak that he reportedly favored, though this name was never officially used in his titles.

Caracalla grew up in a period of intense political upheaval. His father, Septimius Severus, seized power during the tumultuous "Year of the Five Emperors" in 193 CE and established himself as a strong military leader. Caracalla, as Severus' eldest son, was groomed for leadership from an early age. He accompanied his father on military campaigns and was given significant responsibilities as a teenager, including being named Caesar in 195 CE, a title that marked him as the heir to the imperial throne.

Caracalla’s relationship with his younger brother, Geta, was strained from the beginning. The rivalry between the two brothers was encouraged, if not exacerbated, by their mother, Julia Domna, who saw them as competitors for power. This sibling rivalry would eventually culminate in a tragic and bloody episode shortly after they assumed joint control of the empire.

Joint Rule with Geta

Following the death of Septimius Severus in 211 CE, Caracalla and Geta were proclaimed co-emperors, as their father had intended. Severus had hoped that his sons would rule together harmoniously, a vision enshrined in his famous deathbed advice: "Be harmonious, enrich the soldiers, and scorn all other men." However, the deep-seated animosity between the brothers made such a co-rule untenable.

The division between Caracalla and Geta was not just personal but also political. While Caracalla was aggressive and militaristic, favoring a centralized and autocratic style of governance, Geta was more inclined toward a traditional, senatorial approach. This ideological clash only heightened their mutual distrust. The two brothers reportedly divided the imperial palace into separate living quarters, avoided each other in public, and even contemplated splitting the empire into two separate realms. Caracalla was given control over the western provinces, while Geta was assigned the east. Despite their father's wishes, the situation rapidly deteriorated into a power struggle that could not be resolved peacefully.

The tension reached its climax in December 211 CE. Caracalla, determined to eliminate his rival, orchestrated a plot to murder Geta. According to contemporary sources, Geta was lured to a meeting under the pretense of reconciliation, only to be brutally assassinated in the presence of their mother, Julia Domna. Geta was killed by Caracalla's loyal guards, and his mother, who had attempted to shield him, was powerless to stop the attack. This act of fratricide shocked Rome and marked the beginning of Caracalla's sole rule.

Following Geta's assassination, Caracalla launched a campaign of purges against his brother’s supporters and anyone who might oppose his rule. This purge was particularly brutal, with estimates suggesting that as many as 20,000 people were killed in the aftermath. Geta’s memory was subjected to a damnatio memoriae, a practice in which all public records, images, and references to the deceased were destroyed or defaced. Caracalla sought to erase his brother’s existence from history, an attempt that was only partially successful, given the historical records that survived.

The Constitutio Antoniniana

One of Caracalla's most enduring legacies is the Constitutio Antoniniana, or the Antonine Constitution, issued in 212 CE. This sweeping edict granted Roman citizenship to nearly all free inhabitants of the Roman Empire, a dramatic expansion of a privilege that had previously been limited to a much smaller, more exclusive group. The Constitutio Antoniniana is often viewed as one of the most significant legal reforms in Roman history, with far-reaching implications for the social and political fabric of the empire.

Before this edict, Roman citizenship was a coveted status that conferred numerous legal, social, and economic benefits, including the right to own property, marry legally, and appeal to the emperor in legal cases. The decision to extend citizenship to nearly all free men and women within the empire can be seen as both a practical and ideological move. Practically, the edict allowed Caracalla to increase the tax base, as Roman citizens were subject to certain taxes that non-citizens were not. Ideologically, the edict could be interpreted as a move toward greater inclusivity and unity within the empire, reflecting a vision of a more cohesive and homogeneous Roman identity.

However, the motivations behind the Constitutio Antoniniana were not purely altruistic. Caracalla was also seeking to consolidate his power by creating a broader base of loyal subjects who might support his autocratic rule. By making citizenship more widespread, he aimed to secure the loyalty of newly enfranchised citizens, especially in the provinces. This move also allowed him to placate the military, as many soldiers who were provincials would now be granted the rights and privileges of citizenship, further solidifying their loyalty.

The consequences of this edict were profound. It effectively erased the legal distinctions between Italians and provincials, making the empire more uniform in terms of legal status. This shift contributed to the gradual decline of traditional Roman elites, as the distinction between old Roman families and new citizens became less relevant. In the long term, the Constitutio Antoniniana played a crucial role in the transformation of the Roman Empire from a city-state with conquered territories into a more integrated and cosmopolitan state.

Military Campaigns and Expansion

Caracalla's reign was characterized by a series of military campaigns aimed at consolidating and expanding Rome's frontiers. He was deeply influenced by the military ethos of his father, and much of his rule was focused on ensuring the loyalty of the legions and maintaining the strength of the Roman army.

One of Caracalla’s most significant military campaigns was his invasion of Parthia, Rome’s long-standing eastern rival. In 214 CE, he launched a campaign against the Parthian Empire, initially under the guise of seeking a marriage alliance with the Parthian royal family. When the Parthian king, Artabanus IV, refused the proposal, Caracalla used this as a pretext to launch a full-scale invasion. His forces sacked the Parthian city of Arbela, and he declared himself the conqueror of the Parthians, though his victory was not as decisive as he portrayed it to be.

Caracalla’s Parthian campaign is often criticized by historians as being more about personal glory than strategic necessity. His actions alienated the Parthians and destabilized the region, leading to continued conflict along Rome’s eastern borders. However, the campaign also reinforced his image as a warrior-emperor, a role he actively cultivated throughout his reign.

In addition to his eastern campaigns, Caracalla spent significant time and resources maintaining the empire's frontiers, particularly along the Rhine and Danube rivers. He personally led military expeditions into Germania and sought to secure Rome's northern borders against Germanic tribes. His frequent presence with the legions and his efforts to improve their pay and conditions earned him the loyalty of the army, which became the cornerstone of his power.

Caracalla also extended the Roman military presence in Africa, where he sought to strengthen Rome’s control over the desert tribes and protect the vital grain supply routes from Egypt to Rome. His campaigns in North Africa were less about expansion and more about securing the stability of the region, which was crucial for the empire's food security.

Architectural and Cultural Contributions

Caracalla is perhaps best known for the massive bath complex he commissioned in Rome, known as the Baths of Caracalla. These baths, which began construction in 211 CE and were completed during his reign, are among the most impressive examples of Roman engineering and architecture. Covering an area of 27 acres, the Baths of Caracalla included not only the standard bathing facilities but also gardens, libraries, gymnasiums, and spaces for social and cultural activities. The complex could accommodate up to 1,600 bathers at a time, making it one of the largest and most luxurious public bathhouses in the ancient world.

The baths were a testament to Caracalla’s desire to leave a lasting legacy in the capital and to reinforce his connection to the people of Rome. Public baths were an integral part of Roman social life, and by providing such an extravagant facility, Caracalla sought to endear himself to the urban population. The Baths of Caracalla remained in use for several centuries and are still a major archaeological site in Rome today.

Culturally, Caracalla also promoted the cult of the Egyptian god Serapis, continuing a trend initiated by his father. He sought to integrate various religious practices within the empire, reflecting the increasingly diverse and cosmopolitan nature of Roman society. Caracalla’s reign, however, was not marked by significant artistic or literary achievements, as his focus was primarily on military and political matters.

The Massacre of Alexandria

One of the darkest episodes of Caracalla’s reign was the massacre of the population of Alexandria in 215 CE. The exact reasons for this atrocity are unclear, but it is generally believed that it was in retaliation for insults and mockery directed at Caracalla by the Alexandrian populace. The city of Alexandria had a long history of being a center of intellectual and cultural life, but it was also known for its sharp wit and irreverent attitude towards authority.

According to ancient sources, Caracalla, already enraged by the perceived slights, invited the city’s leading citizens to a banquet, ostensibly to demonstrate his goodwill. Instead, he ordered his soldiers to slaughter the attendees and then unleashed his legions on the city, resulting in widespread carnage. The massacre left a deep scar on the city and is one of the most notorious acts of brutality in Caracalla's reign.

The massacre of Alexandria exemplifies Caracalla’s tendency to react with extreme violence to any challenge or insult. His brutal methods ensured that he was feared throughout the empire, but they also earned him the enmity of many, contributing to the instability that would follow his reign.

Assassination and Aftermath

Caracalla’s reign came to a violent end on April 8, 217 CE, when he was assassinated near the city of Carrhae in present-day Turkey. The assassination was orchestrated by the Praetorian Prefect, Macrinus, who had become increasingly concerned for his own safety under Caracalla’s unpredictable and tyrannical rule. The immediate cause of the assassination was reportedly Caracalla’s plan to execute Macrinus, who preemptively struck by organizing a plot with disaffected members of the imperial entourage.

While traveling with his army, Caracalla stopped to relieve himself by the roadside, where he was attacked and killed by a soldier named Martialis, who was part of the conspiracy. Caracalla’s assassination ended the Severan dynasty’s direct line, as he left no surviving legitimate heirs. Macrinus quickly proclaimed himself emperor, marking the beginning of a brief and unstable period in Roman history.

Caracalla’s death did not lead to immediate stability. Macrinus, despite his role in Caracalla’s assassination, struggled to maintain control and was eventually overthrown by a faction supporting Elagabalus, a young relative of Caracalla, who claimed to be his illegitimate son. The Severan dynasty continued for a few more years, but the instability and internal strife that characterized Caracalla’s reign persisted, contributing to the eventual decline of the dynasty and the Roman Empire’s entry into the Crisis of the Third Century.

Caracalla’s legacy is a deeply ambivalent one. On the one hand, his Constitutio Antoniniana stands as a monumental achievement in Roman law, symbolizing the inclusivity and universality of Roman citizenship. This reform had long-lasting effects, shaping the social and legal structure of the Roman Empire and contributing to the empire’s cohesion.

On the other hand, Caracalla’s reign is also remembered for its extreme violence, political purges, and acts of cruelty. His fratricide, the massacre of Alexandria, and his ruthless suppression of dissent have left an indelible stain on his reputation. While he was successful in securing the loyalty of the army and maintaining the stability of the empire during his lifetime, his methods of governance sowed the seeds of future instability.

Caracalla’s rule is a reflection of the complexities of power in the Roman Empire during a time of transition. He was a ruler who sought to strengthen and unify the empire, yet his brutal tactics and disregard for traditional republican values also highlighted the growing autocracy that characterized the later Roman Empire. In the end, Caracalla remains one of the more controversial figures in Roman history, a man whose vision for the empire was as ambitious as it was ruthless.

Caracalla, the son of Emperor Septimius Severus, is often remembered as one of Rome's most brutal and capricious rulers. Raised in an atmosphere of imperial power, he displayed a violent and unpredictable nature from a young age. A defining moment of his reign was the murder of his brother, Geta, with whom he had initially shared power. This act of fratricide plunged the empire into further instability. Caracalla is also known for his lavish spending, particularly on public works projects such as the Baths of Caracalla.

Despite his tyrannical reputation, Caracalla's reign was not without significant developments. His most enduring legacy is the Antonine Constitution, which granted Roman citizenship to all free-born inhabitants of the empire. This edict had far-reaching implications, unifying the empire under a single legal framework. However, this achievement is often overshadowed by his cruelty and extravagance, leaving a complex and contradictory image of his reign.

Latest

Popular

Useful