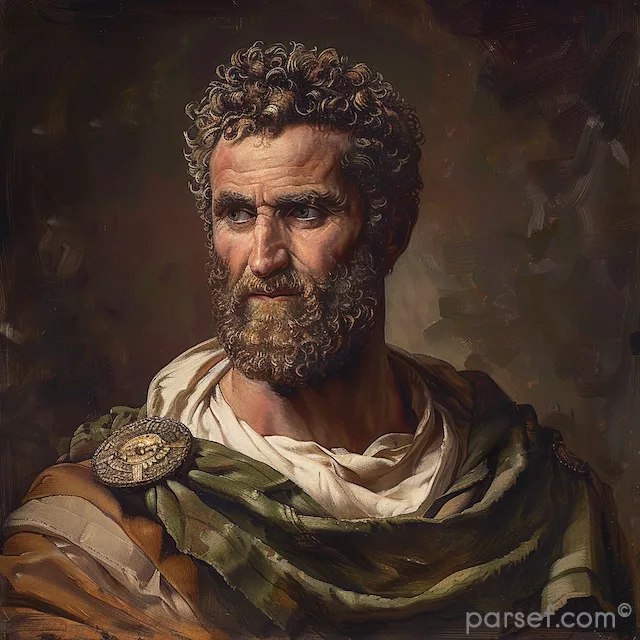

Roman Emperor Severus Alexander (222-235 CE)

Severus Alexander: The Last of the Severan Dynasty

Severus Alexander, born Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander on October 1, 208 CE, was the last emperor of the Severan dynasty and the last ruler of the Roman Empire before the onset of the Crisis of the Third Century. His reign, which lasted from 222 to 235 CE, was characterized by attempts to restore stability to the Roman state after the tumultuous and scandalous rule of his cousin Elagabalus. Despite his youth, Severus Alexander sought to govern wisely with the guidance of his grandmother, Julia Maesa, and his mother, Julia Mamaea. However, his reign ultimately ended in tragedy, as he was unable to meet the growing challenges of a restless military and a politically unstable empire. Severus Alexander’s life and rule offer a poignant glimpse into the struggles of leadership during a critical period in Roman history.

Early Life and Rise to Power

Severus Alexander was born in Arca Caesarea, a town in the Roman province of Syria, into the influential Severan family. His father, Gessius Marcianus, was a Roman noble of equestrian rank, but it was through his mother, Julia Mamaea, that Severus Alexander was connected to the ruling dynasty. Julia Mamaea was the niece of Julia Domna, the wife of Emperor Septimius Severus, and the sister of Julia Soaemias, the mother of Elagabalus. This connection to the Severan dynasty would prove crucial in Alexander’s rise to power.

As a child, Severus Alexander was brought to Rome and raised in the imperial court under the watchful eyes of his grandmother, Julia Maesa, and his mother. Both women were deeply involved in the political machinations of the Severan dynasty, and they ensured that young Alexander received a thorough education in rhetoric, philosophy, and law. He was known for his intelligence, modesty, and dedication to learning, qualities that would later define his approach to governance.

In 218 CE, Elagabalus, Alexander’s cousin, was proclaimed emperor after the assassination of Emperor Macrinus. Elagabalus’s reign quickly descended into chaos as he sought to impose his religious beliefs on the Roman populace and engaged in scandalous behavior that alienated the Senate, the military, and the general population. Julia Maesa, recognizing the growing discontent with Elagabalus’s rule, began to groom Severus Alexander as a potential successor.

In 221 CE, under pressure from the Praetorian Guard and his grandmother, Elagabalus was forced to adopt Severus Alexander as his heir. The young Alexander was given the title of Caesar, making him the designated successor to the throne. This move was intended to placate the military and stabilize the empire, but it only delayed the inevitable. In March 222 CE, the Praetorian Guard, fed up with Elagabalus’s erratic behavior, turned against him. Elagabalus and his mother were murdered by the guards, and Severus Alexander was immediately declared emperor.

The Early Reign: A New Beginning

Severus Alexander ascended to the throne at the age of 13, making him one of the youngest emperors in Roman history. His reign was initially dominated by his grandmother, Julia Maesa, and his mother, Julia Mamaea, both of whom acted as regents and wielded significant influence over imperial affairs. These powerful women were determined to restore the stability and dignity of the Roman Empire, which had been tarnished by the excesses of Elagabalus’s rule.

One of the first acts of Severus Alexander’s reign was to distance himself from the controversial policies of his predecessor. The young emperor restored the traditional Roman religious practices, reaffirming the primacy of the Roman gods and minimizing the influence of the cult of Elagabal. He also sought to reestablish good relations with the Senate and the aristocracy, who had been alienated by Elagabalus’s disregard for tradition and decorum. Severus Alexander adopted a more moderate and conciliatory approach to governance, earning the respect of many in Rome’s elite.

Severus Alexander’s reign was marked by efforts to promote justice, efficiency, and morality within the empire. He surrounded himself with advisors who were chosen for their experience and wisdom rather than their personal loyalty, a departure from the nepotism and favoritism that had characterized the courts of previous emperors. One of his most trusted advisors was the jurist Ulpian, who played a key role in reforming the legal system and promoting a sense of equity and fairness in the administration of justice.

Domestic Policy and Governance

Severus Alexander’s domestic policies reflected his desire to stabilize the empire and improve the lives of its citizens. He implemented a series of reforms aimed at reducing corruption and inefficiency within the imperial administration. To this end, he sought to streamline the bureaucracy, reduce the burden of taxes on the provinces, and curtail the extravagant spending that had depleted the imperial treasury.

One of Severus Alexander’s notable domestic policies was his emphasis on public works and infrastructure. He invested in the maintenance and expansion of Rome’s road network, aqueducts, and public buildings, recognizing the importance of these projects for the well-being and prosperity of the empire. His reign saw the construction and renovation of numerous temples, baths, and civic buildings, contributing to the revitalization of Rome and its provinces.

Severus Alexander also took measures to address the welfare of the Roman people. He expanded the cura annonae, the grain dole that provided free or subsidized grain to the urban poor, ensuring that the people of Rome had access to food during times of scarcity. Additionally, he supported education and the arts, promoting intellectual and cultural life within the empire.

Despite these efforts, Severus Alexander faced significant challenges in maintaining control over the empire. The Roman economy was under strain due to the high costs of maintaining the military and the imperial bureaucracy. Inflation and currency debasement were ongoing issues, and the emperor’s attempts to address these problems were only partially successful. Moreover, the growing power of the military, which had become increasingly influential in imperial politics, posed a constant threat to his authority.

Foreign Policy and Military Challenges

Severus Alexander’s reign was marked by significant military challenges on the empire’s frontiers. The most pressing of these challenges came from the Sassanian Empire, a newly established power in Persia that had replaced the Parthian Empire as Rome’s primary eastern rival. The Sassanian king, Ardashir I, launched a series of aggressive campaigns against Roman territories in the East, threatening the empire’s hold on Mesopotamia and the eastern provinces.

In 231 CE, Severus Alexander embarked on a military campaign to confront the Sassanian threat. Despite his lack of military experience, he personally led the Roman forces in an attempt to repel the Sassanian incursions. The campaign, however, was only partially successful. While the Romans were able to halt the Sassanian advance and stabilize the eastern frontier, they were unable to achieve a decisive victory. The conflict with the Sassanians remained unresolved, contributing to the ongoing instability in the region.

Severus Alexander also faced challenges on the empire’s northern frontiers, particularly from the Germanic tribes along the Rhine and Danube rivers. In 234 CE, these tribes began a series of raids and incursions into Roman territory, threatening the security of the empire’s northern provinces. Severus Alexander responded by organizing a military expedition to the region, but his handling of the situation revealed his weaknesses as a military leader.

Rather than engaging the Germanic tribes in battle, Severus Alexander sought to negotiate with them, offering them financial subsidies in exchange for peace. This approach was perceived as a sign of weakness by the Roman legions, who were frustrated by the lack of decisive action. The troops, already discontented with the emperor’s leadership and influenced by the growing power of their commanders, began to lose confidence in Severus Alexander’s ability to protect the empire.

The Downfall: Mutiny and Assassination

The growing discontent within the military, combined with the perception that Severus Alexander was too heavily influenced by his mother and lacked the decisive qualities of a strong emperor, ultimately led to his downfall. The situation came to a head in 235 CE, when Severus Alexander and his mother were encamped with the Roman army near Mogontiacum (modern-day Mainz, Germany) during the campaign against the Germanic tribes.

As the discontent among the troops reached a boiling point, a mutiny erupted. The soldiers, led by their commanders, turned against Severus Alexander, accusing him of weakness and ineffectiveness in dealing with the empire’s enemies. On March 19, 235 CE, Severus Alexander and his mother were murdered by their own troops, who proclaimed Gaius Julius Verus Maximinus, a popular general known as Maximinus Thrax, as the new emperor.

The assassination of Severus Alexander marked the end of the Severan dynasty and the beginning of a period of intense instability known as the Crisis of the Third Century. This era was characterized by frequent changes of emperors, civil wars, economic decline, and external invasions, all of which threatened the very survival of the Roman Empire.

Legacy

Severus Alexander’s legacy is a complex one, shaped by his attempts to restore stability and order to the Roman Empire during a time of great difficulty. As the last ruler of the Severan dynasty, he represented the final effort of that family to govern the empire according to its principles of moderation, legal reform, and respect for Roman traditions.

Severus Alexander’s reign is often viewed with sympathy by historians, who see him as a well-intentioned but ultimately ineffective ruler. His youth, inexperience, and reliance on his mother and advisors left him vulnerable to the pressures of the military and the challenges of ruling a vast and increasingly fractious empire. Despite his best efforts to maintain the stability of the empire, he was ultimately unable to withstand the forces that were tearing it apart.

In the broader context of Roman history, Severus Alexander’s reign serves as a poignant reminder of the challenges faced by emperors during the late Roman Empire. His assassination and the subsequent chaos that engulfed the empire illustrate the precarious nature of imperial power and the difficulties of maintaining control over a diverse and expansive realm. Severus Alexander’s death marked the end of an era, and his memory, though overshadowed by the crises that followed, remains a testament to the complexities of leadership in one of history’s greatest empires.

Severus Alexander ascended to the Roman throne at a tender age, following the tumultuous reign of his cousin, Elagabalus. Raised by his strong-willed mother, Julia Mamaea, he was presented as a young and virtuous emperor, a stark contrast to his predecessor's excesses. Alexander was known for his intellectual pursuits, interest in philosophy, and attempts at reforming the empire. He sought to restore fiscal stability, improve relations with the Senate, and address the growing threat of barbarian invasions. However, his reign was also marked by indecision and a reliance on his mother's counsel, which alienated many.

Despite his good intentions, Alexander's reign was ultimately unsuccessful. The empire faced increasing economic and military challenges, and the young emperor lacked the experience and charisma to effectively address them. His reliance on advisors and his reluctance to make tough decisions weakened his authority. Ultimately, his downfall came at the hands of his own troops, who were dissatisfied with his leadership and attracted to the more martial qualities of Maximinus Thrax. Alexander's assassination marked the end of the Severan dynasty and ushered in the chaotic period known as the Crisis of the Third Century.

Latest

Popular

Useful