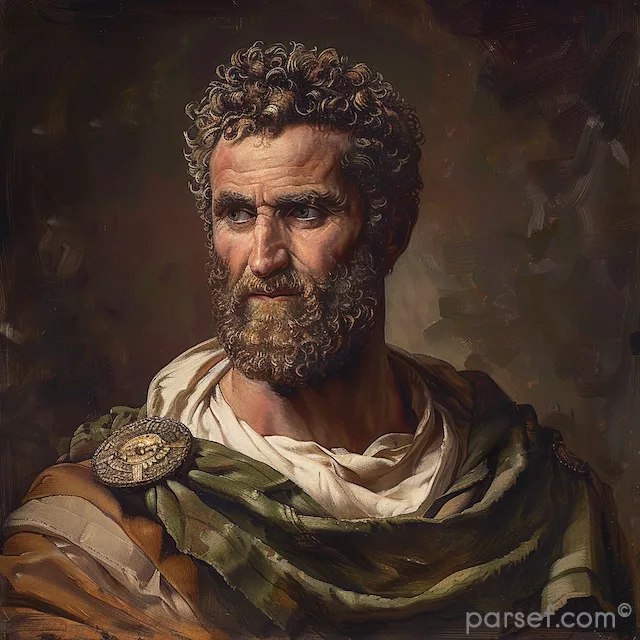

Roman Emperor Macrinus (217-218 CE)

Macrinus: The First Non-Senatorial Roman Emperor

Marcus Opellius Macrinus, commonly known as Macrinus, occupies a unique place in Roman history as the first Roman emperor to rise to power without having previously held a senatorial rank. His brief reign, lasting from 217 to 218 CE, was marked by his attempts to manage the Roman Empire’s complex political and military challenges, as well as his efforts to distance himself from the controversial reign of his predecessor, Caracalla. Despite his initial success in securing the imperial throne, Macrinus’s lack of aristocratic pedigree and military experience, combined with growing discontent among the Roman legions and the machinations of the Severan dynasty’s supporters, ultimately led to his downfall.

Early Life and Rise to Power

Macrinus was born around 164 CE in Caesarea, a city in the Roman province of Mauretania Caesariensis, which corresponds to modern-day Algeria. His origins were humble compared to most Roman emperors; he was of equestrian rank rather than senatorial, making his rise to the throne all the more remarkable. Macrinus came from a relatively obscure provincial family, and little is known about his early life. He likely received a solid education, which enabled him to pursue a career in the Roman legal system, where he gained a reputation for his administrative abilities and legal expertise.

By the early 200s CE, Macrinus had risen to prominence in the imperial administration, serving as a procurator and eventually securing a position as the praefectus praetorio (Praetorian Prefect) under Emperor Caracalla. This role was one of the most powerful in the empire, as the Praetorian Prefect commanded the Praetorian Guard, the elite force responsible for the emperor’s protection, and wielded significant influence over military and judicial matters. Macrinus's appointment to this position reflects Caracalla’s trust in his abilities, but it also placed him in a precarious position, as the emperor was known for his paranoia and ruthlessness.

Conspiracy and Assassination of Caracalla

Caracalla's reign (211–217 CE) was marked by extreme brutality, including the murder of his brother Geta, the massacre of thousands of Roman citizens, and costly military campaigns. By 217 CE, Caracalla was deeply unpopular with many segments of Roman society, including the Senate, the military, and the general populace. His aggressive foreign policy, particularly his campaigns against the Parthian Empire, placed significant strains on the empire's resources and alienated many within the military.

Macrinus, like many others, had become increasingly concerned about Caracalla's erratic behavior. Fearing for his own life, as Caracalla had a history of executing those he perceived as threats, Macrinus became involved in a conspiracy to assassinate the emperor. The exact details of the plot are murky, but it is widely believed that Macrinus played a central role in orchestrating Caracalla's murder.

On April 8, 217 CE, while Caracalla was traveling near the city of Carrhae in present-day Turkey, he was assassinated by a soldier named Martialis, who was likely acting on Macrinus's orders. Caracalla’s death left a power vacuum, and within days, the legions proclaimed Macrinus as the new emperor. His ascension marked a significant departure from tradition, as Macrinus was the first Roman emperor who was not of senatorial rank, setting a precedent for the elevation of men from outside the traditional aristocracy.

Reign of Macrinus

Macrinus’s reign began with a sense of cautious optimism. As a seasoned administrator and jurist, he was well aware of the challenges facing the empire. His primary objectives were to stabilize the empire's finances, restore discipline within the military, and negotiate peace with Rome's external enemies, particularly the Parthians.

Military and Foreign Policy

One of Macrinus's first major actions as emperor was to seek peace with the Parthian Empire. Caracalla’s aggressive campaigns had strained the empire’s resources and alienated many within the military, who were weary of the continuous warfare. Macrinus recognized that the ongoing conflict was unsustainable, and he quickly moved to negotiate a peace settlement. In 217 CE, he reached an agreement with the Parthian king, Artabanus IV, which involved paying a substantial indemnity to the Parthians in exchange for peace. While this treaty brought an end to the hostilities, it was unpopular among the Roman legions, who viewed it as a humiliating concession and a sign of weakness.

Macrinus’s attempts to restore discipline within the army also faced significant resistance. He sought to reduce the pay and privileges that Caracalla had lavishly granted to the soldiers in an attempt to curry favor with them. These measures, although necessary to stabilize the empire's finances, further alienated the troops, who had grown accustomed to the generous rewards under Caracalla’s rule. The discontent within the military would prove to be a critical factor in Macrinus's downfall.

Economic and Administrative Reforms

On the domestic front, Macrinus took steps to address the empire’s financial difficulties. Caracalla’s extravagant spending on public games, building projects, and the military had left the empire in a precarious economic situation. Macrinus implemented a series of cost-cutting measures, including reducing the pay of the soldiers and curtailing unnecessary expenditures. He also sought to reform the tax system to increase revenues and reduce the burden on the provinces. These reforms, however, were met with resistance from both the military and the provincial elites, who had benefited from the previous regime's largesse.

Despite his efforts to restore fiscal stability, Macrinus struggled to gain the support of the Senate and the Roman aristocracy. As an equestrian and a relative outsider, he lacked the connections and influence that previous emperors had used to secure their position. The Senate, which had been sidelined during Caracalla’s reign, viewed Macrinus with suspicion and was reluctant to fully endorse his authority.

The Rise of Elagabalus and Macrinus’s Downfall

Macrinus’s position became increasingly precarious as opposition to his rule grew. The turning point came in 218 CE when a rebellion broke out in the eastern provinces. The revolt was led by Julia Maesa, the sister of Julia Domna (the wife of Septimius Severus and mother of Caracalla), who sought to restore the Severan dynasty to power. Julia Maesa promoted her fourteen-year-old grandson, Varius Avitus Bassianus, better known as Elagabalus, as the legitimate heir to the throne, claiming that he was the illegitimate son of Caracalla.

Elagabalus was proclaimed emperor by the legions stationed in Syria, and the rebellion quickly gained momentum. Macrinus, recognizing the threat posed by this insurrection, attempted to quell the uprising by sending troops to confront the rebel forces. However, his efforts were hampered by the widespread discontent within the army, and many soldiers defected to Elagabalus’s cause.

In June 218 CE, Macrinus faced Elagabalus’s forces in the Battle of Antioch. The battle was a decisive defeat for Macrinus, as his troops, demoralized and disillusioned, either deserted or were overwhelmed by the enemy. Macrinus fled the battlefield and attempted to escape to the west, but he was captured in Chalcedon (modern-day Kadıköy, Turkey) while trying to reach Rome. Shortly thereafter, he was executed on June 8, 218 CE, along with his son Diadumenianus, who had been named co-emperor during Macrinus's reign.

Legacy

Macrinus’s reign, though brief, is significant for several reasons. As the first emperor to come from an equestrian background, his rise to power marked a departure from the traditional senatorial aristocracy that had dominated the imperial office. His attempts to stabilize the empire’s finances and negotiate peace with Rome’s enemies demonstrate his pragmatic approach to governance, even if these efforts were ultimately unsuccessful.

However, Macrinus's reign also highlights the inherent difficulties faced by an emperor who lacked strong support from the military and the aristocracy. His inability to win the loyalty of the legions and his failure to cultivate a base of support among the senatorial elite left him vulnerable to the kind of political and military challenges that ultimately led to his downfall.

In the end, Macrinus’s reign is often viewed as an interlude between the more prominent reigns of Caracalla and Elagabalus. His assassination and the restoration of the Severan dynasty by Elagabalus marked a return to the more flamboyant and autocratic style of rule that characterized the period. Nevertheless, Macrinus’s brief tenure as emperor remains a fascinating chapter in the history of the Roman Empire, illustrating both the possibilities and limitations of social mobility in the ancient world, as well as the volatile nature of Roman imperial politics.

Macrinus was an unusual emperor. Unlike his predecessors, he didn't hail from the traditional senatorial class. A career military man, he rose through the ranks to become Praetorian Prefect under Caracalla. His reign began unexpectedly when he orchestrated the assassination of Caracalla. This drastic action, while securing his position, alienated many in the empire. Despite his lack of noble lineage, Macrinus proved to be a capable administrator. He implemented financial reforms to stabilize the economy and sought to improve relations with the Senate.

However, Macrinus faced significant challenges. The army, accustomed to the Severan dynasty, was discontent. His decision to end Caracalla's lavish spending further eroded his popularity. Additionally, his military campaign against the Parthians ended in a costly stalemate. These factors, combined with the rise of Elagabalus as a charismatic and popular alternative, led to a rapid decline in Macrinus' support. Ultimately, he was defeated in battle and executed, marking a brief interlude in the tumultuous history of the Roman Empire.

Latest

Popular

Useful