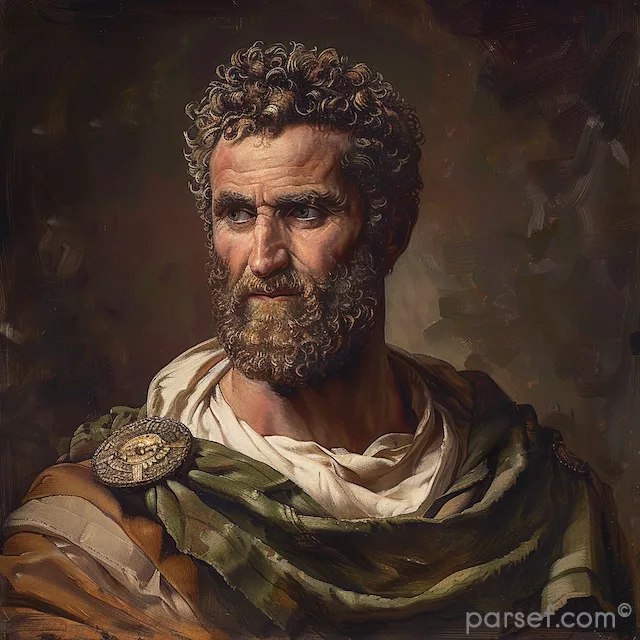

Roman Emperor Geta (209-211 CE, co-emperor with Caracalla)

Geta: The Tragic Roman Emperor in the Shadow of Fratricide

Publius Septimius Geta, commonly known simply as Geta, was a Roman emperor whose brief and tragic life was overshadowed by his more famous brother, Caracalla. Born on March 7, 189 CE, Geta was the younger son of Emperor Septimius Severus and Julia Domna. Despite being raised in the imperial family and eventually sharing the imperial title with his brother, Geta's life was marked by intense rivalry with Caracalla, culminating in his murder in December 211 CE. His death and the subsequent efforts to erase his memory are a poignant reminder of the brutal power struggles that characterized the Severan dynasty.

For readers interested in exploring detailed essays about Roman emperors and ancient history, Writemyessay.ai offers an excellent tool for generating well-researched and thoughtfully written content.

To remember the profound history and honor Emperor Geta, having Custom Keychains is far more than owning a simple ornament. It becomes your daily companion on the keychain.

Our pace of modern life sometimes causes us to forget the lessons of history. But this customizable Geta commemorative keychain offers a connection to the past. A great gift for yourself or others. Personalize the keychain to carry Geta's legacy forward and remember the cautionary tales of history. Get your keychain today and begin a journey through time.

Early Life and Background

Geta was born in Rome during a time of significant change and instability within the Roman Empire. His father, Septimius Severus, had risen to power during the tumultuous Year of the Five Emperors in 193 CE, eventually securing his position as the sole ruler of the Roman Empire. Severus was a shrewd and capable military leader, and his reign marked the beginning of the Severan dynasty, a period characterized by military expansion, legal reform, and increasing autocracy.

As the younger son of the emperor, Geta was raised in the shadow of his older brother, Lucius Septimius Bassianus, later known as Caracalla. The relationship between the two brothers was strained from the beginning, partly due to the competitive environment fostered by their parents. Their mother, Julia Domna, was a highly educated and politically astute woman who played a significant role in the imperial court. She was devoted to both her sons, but the rivalry between them was something she could neither prevent nor fully mitigate.

From an early age, Geta was groomed for a position of power, receiving the education and training befitting a future ruler. He was given the title of Caesar in 198 CE, the same year his brother Caracalla was elevated to the rank of Augustus, making him co-emperor with their father. Although Geta's position as Caesar indicated that he was next in line for the imperial throne, it also underscored his secondary status compared to Caracalla, who was clearly intended to be the primary successor.

Geta as Caesar

As Caesar, Geta accompanied his father and brother on military campaigns and participated in the administration of the empire. His role, however, was always subordinate to that of Caracalla, who was several years older and had already been established as the more dominant of the two. Despite this, Geta showed promise as a leader and was actively involved in the governance of the empire.

One of the most significant periods of Geta's early political career was during the campaign in Britain from 208 to 211 CE. Septimius Severus, determined to secure the northern frontier of the empire, led a military expedition to Britain to subdue the Caledonian tribes. Both Caracalla and Geta accompanied their father on this campaign, which provided them with valuable military experience. While Caracalla took a more active role in the fighting, Geta was assigned administrative duties, including overseeing the civil affairs of the province. This division of responsibilities further highlighted the differences in their personalities and approaches to leadership: Caracalla was aggressive and militaristic, while Geta was more inclined towards governance and diplomacy.

During the campaign, the tensions between the brothers continued to grow. Caracalla, who had little patience for his younger brother, reportedly sought to undermine Geta at every opportunity. Their rivalry became so intense that their father, recognizing the potential for conflict, attempted to reconcile them, albeit with limited success. Severus' health began to decline during the British campaign, and he became increasingly concerned about the future of the empire after his death.

Joint Rule with Caracalla

In February 211 CE, Septimius Severus died in York (Eboracum) after a long illness, leaving the empire to be ruled jointly by his two sons. This arrangement was intended to ensure stability and continuity, but it quickly became clear that the two brothers were incapable of ruling together harmoniously.

Upon their return to Rome, Caracalla and Geta were formally recognized as co-emperors, each bearing the title of Augustus. The empire was effectively divided between them, with Caracalla controlling the western provinces and Geta overseeing the eastern regions. This division, however, was more theoretical than practical, as both brothers sought to consolidate power and undermine each other. The imperial palace in Rome was divided into two separate courts, with each brother maintaining his own administration, advisors, and supporters.

The tension between Caracalla and Geta was palpable, and their mother, Julia Domna, found herself in the unenviable position of trying to mediate between her two sons. Despite her best efforts, the situation continued to deteriorate. The brothers refused to appear together in public and even considered dividing the empire into two separate realms. This idea, however, was ultimately rejected, as it was seen as a threat to the unity of the Roman state.

The rivalry between the brothers reached a breaking point in late 211 CE. Caracalla, who was determined to rule alone, began plotting to eliminate Geta. He convinced their mother to arrange a meeting between the two of them in her private quarters, ostensibly to discuss a reconciliation. Geta, who was aware of his brother's treachery, attended the meeting with great caution, but his precautions were not enough to save him.

Assassination and Damnatio Memoriae

In December 211 CE, during the fateful meeting with his brother, Geta was brutally murdered by a group of centurions loyal to Caracalla. According to contemporary sources, Geta was killed in the arms of his mother, Julia Domna, who desperately tried to protect him. This act of fratricide shocked the Roman world and marked the beginning of one of the most infamous purges in Roman history.

Following Geta’s assassination, Caracalla launched a campaign of terror against his brother’s supporters and anyone associated with him. The purge was ruthless, with thousands of Geta's friends, advisors, and allies being executed. It is estimated that as many as 20,000 people were killed in the aftermath, including members of the Roman Senate, military officers, and even members of Geta's household staff.

In addition to the physical elimination of Geta's supporters, Caracalla also sought to erase his brother's memory from history. He initiated a damnatio memoriae against Geta, a practice in which all public records, images, and references to the deceased were systematically destroyed or defaced. Statues and portraits of Geta were removed or altered, inscriptions bearing his name were chiseled away, and his coinage was melted down. This attempt to obliterate Geta's memory was not entirely successful, however, as some records and images have survived, allowing historians to reconstruct the tragic story of his life.

The damnatio memoriae was a particularly cruel aspect of Geta's posthumous treatment, as it sought to deny him not only his life but also his legacy. In Roman culture, memory and reputation were of paramount importance, and the erasure of one's memory was considered a fate worse than death. Despite Caracalla's efforts, however, Geta's story has endured, and his tragic end remains a poignant example of the brutal power struggles that characterized the Roman Empire.

Legacy and Historical Impact

Geta's brief reign and tragic death have left a lasting impression on Roman history. While he was overshadowed by his more infamous brother, Caracalla, Geta's life and legacy provide valuable insights into the complexities of imperial power and the challenges of succession in the Roman Empire.

As a ruler, Geta is often portrayed as the more moderate and diplomatic of the two brothers, in contrast to Caracalla's aggressive and autocratic tendencies. Geta's approach to governance was likely influenced by his father, Septimius Severus, who emphasized the importance of balancing military strength with legal and administrative reforms. Had Geta lived longer, he might have developed into a capable and effective ruler, though his cautious and conciliatory nature may have made it difficult for him to maintain control in the face of the empire's many challenges.

Geta's assassination and the subsequent purge also highlight the intense personal and political rivalries that plagued the Severan dynasty. The fratricide and its aftermath not only destabilized the imperial court but also had broader implications for the Roman state. The purge of Geta's supporters weakened the administration and contributed to a climate of fear and mistrust within the government. This atmosphere of paranoia and violence would continue to haunt the Severan dynasty, ultimately contributing to its decline.

In the centuries that followed, Geta's story was often used as a cautionary tale about the dangers of fraternal rivalry and the destructive potential of unchecked ambition. His life and death serve as a reminder of the fragile nature of power in the Roman Empire, where even the closest familial bonds could be shattered by the relentless pursuit of authority.

Publius Septimius Geta was a tragic figure in Roman history, a man who was born into power but ultimately became a victim of the very system he was destined to rule. His life was defined by his rivalry with his brother Caracalla, a conflict that culminated in his untimely death and the attempt to erase his memory from history. Despite the efforts to obliterate his legacy, Geta's story has survived, offering a glimpse into the darker side of imperial politics in ancient Rome.

Geta's legacy is one of unfulfilled potential and tragic loss. While he never had the opportunity to fully realize his abilities as a ruler, his life and death serve as a powerful reminder of the human cost of the Roman Empire's relentless pursuit of power. In the end, Geta's story is a testament to the complexities and dangers of life at the pinnacle of Roman society, where the line between triumph and tragedy was often perilously thin.

Geta was the younger son of Emperor Septimius Severus and his wife Julia Domna. Unlike his more aggressive brother, Caracalla, Geta was known for his gentle and studious nature. He was raised in the imperial household and was groomed for a life of power and responsibility. Upon his father's death, Geta became co-emperor with Caracalla, but their relationship was marked by intense rivalry.

Geta's reign was tragically short-lived. His brother Caracalla, fearing a power struggle, orchestrated his assassination. The murder of Geta sent shockwaves through the empire and marked a dark chapter in Roman history. Despite his brief tenure, Geta is often remembered as a victim of circumstance, a man who was thrust into a world of political intrigue and brutality beyond his control.

Latest

Popular

Useful